Hello everyone,

Here is the McElhinny article that Ernesto mentioned in our presentation this last Tuesday.

I am trying to download the Flores and Lewis article. As soon as I get it, I’ll post it.

Hello everyone,

Here is the McElhinny article that Ernesto mentioned in our presentation this last Tuesday.

I am trying to download the Flores and Lewis article. As soon as I get it, I’ll post it.

In this blog I am attempting at linking the theoretical discussion and framework of code-switching as a linguistic phenomenon in CMC as discussed by Hinrichs 2015 to actual authentic examples from my recent personal experience of family loss and dealing with it, and the role of CMC in this regard. Due to cultural differences my examples my seem to have crossed the boundaries of what is unshareably intimate and private. However, in our Arabic culture, we are open to share our sentiments and our experiences of loss and pain with others, just like it is acceptable in another culture to talk about traumatizing experiences of being subjected to rape and sexual assault for example.

In his (2015) paper, Hinrichs proposes that written digital code switching (WDCS) is a product of globalization. He provides an account for code switching (CS) among multidialectal diasporic Jamaican bloggers as a stylistic/ linguistic practice rooted in social power and identities. He argues that WDCS, unlike CS in speech, is more carefully constructed and is marked by rhetoricity which, to him, means figurative language: a language conveying meaning which does not arise from direct reference to objects, but rather from imagery or “semiotic tropes such as metaphor, symbolism, iconicity, simile and metonym…” Figurative language is “more elaborate, unpredictable, creative and artful” requiring cognitive work and reflecting aesthetic principles. Rhetoricity reflects how multiple contrasting linguistic resources are combined in discourse.

Hinrichs cites Gumperz and explains how the latter differentiates between situational and metaphorical CS:

In situational CS, the bilingual/ bi-dialectal speakers/ writers choose the language/ dialect according to their addressee, topic, location, and other situational, psychological, emotional, social and cultural factors, following the bilingual community’s norms dictating which code would be appropriate. Situational CS, which is rare in digital discourse as Hinrichs argues, involves “a simple almost one-to-one relationship between language usage and social context”, de-emphasizing volitional switching. Situational CS is a reaction on the part of the speaker to changes in setting, topic, or addressee. Only few topics in CMD produce correlations with CS in predictable directions.

In metaphorical CS, speakers/ writers switch codes as if a feature/ variable of the situation (addressee, topic, location, etc.) has changed when in reality nothing has changed. Hinrichs argues that it is this type of CS that is used in CMC. It is a focusing device which works through contrast. In this type of CS, the meanings are constructed from “complex juxtapositions of intertextually embedded voices and stances” of others which we assimilate, rework and re-accentuate, according to both Bakhtin and Hinrichs. Hinrichs argues that construction of complex and hybrid voices is the most strongly rhetorical discourse function of CS in general.

Instead of dividing CS to situational and metaphorical, Hinrichs proposes categorizing types of switches into three types based on the notion of voice, intertextuality and heteroglossia. The first group consists of switches that construct meaning from contrast. The second and third groups are more rhetorical: the relation between the codes and the topic as well as the writer’s stance contribute to the interactional meaning.

In the first type, the switches signal to the reader that s/he needs to understand and contextualize stretches expressed in each language or variety differently. Switches between codes are not “jumps to external linguistic resources”; each code is rather an integral part of all the voices the speaker/ writer adopts or expresses.

The second type is the polyvocal CS, in which CS is used in contexts of intertextuality as a result of polyvocality. This type includes “switches through which either textual material form, of the voice of, an identifiable, concreate personal or textual source is integrated.” This includes switching for quotations, and quotations in turn serve different contextual and discourse purposes.

The third type, heteroglossic CS, refers to switches in which the other voice is an opaque source, not a concrete person or text. This type mostly manifests itself at the lexical level and indexes a sociocultural code. An example of this provided in the paper is when a young female narrates a story using one linguistic variety, and then comments on the story using another. This type of CS draws attention to the writer’s linguistic repertoire. Code switchers have access to a range of codes as diverse, different, and distant from one another, as the globalization nature of the communicative environments themselves. CS here reflects alternating between cultures. It is the most rhetorical and figurative type.

In conclusion, Hinrichs argues that the effect of globalization favor greater rhetoricity in WDCS behavior. “The transitional position of diasporic writers leads to more rhetoricity in diasporic writing…Electronic medium itself, as a site and agent of globalization, features rhetoricity.”

As we have seen the paper touches upon the notion of diglossia, which according to Fergurson is the co-existence of two mutually exclusive linguistic varieties of the same language in the same community. Arab communities in general are known to be diglossic with two forms or varieties of Arab, in addition to being bilingual or trilingual in some parts of the Arab world and among certain social groups. These two varieties of Arabic are selected by the speaker/ writer based on the situation, the topic, and the audience, etc. The two varieties are the Modern Standard Arabic MSA and the regional spoken dialect(s). MSA is the form used in writing books, newspaper and magazine articles, and official governmental forms. It is also the linguistic variety used for broadcasting the news on TV and the radio, in political or documentary programs, lecturing (though not always and not everywhere in the Arab world), formal religious ceremonies and other formal and official contexts in which education, politics, literature, or religion… is the core topic. Before the age of globalization and digital communication, writing in MSA was the sole medium for all genres and styles of writing including personal letters and journal entries. The regional spoken dialects which differ from one region to another and even from one socioeconomic stratum to another is (and had solely been before the age of CMC) the medium for conversations/ oral communication among people on everyday topics. Syria is no exclusion to this diglossic situation. Syrians grow up to a certain degree balanced bidialectal, exposed to the Syrian dialect(s) at home through communication with people around them, and to MSA at preschools and schools and through TV programs (including children program until not too long ago). What is interesting is that the beginning of the digital age marks also the beginning of a new linguistic era in which using spoken dialects for informal and personal communication has begun, especially in CMC. No studies are carried out yet to show if the total or partial replacement of MSA with spoken dialects in CMC is a mere coincidence or if it is one of the globalization’s results. Whatever the case is, the move from MSA only as the only means for writing to a mix of MSA and dialects marks a move from the wide socio-political notion of Arab nationalism to a narrower type of nationalism associated with one’s immediate home country and not the whole Arab world.

The paper also is centered on the notion of diaspora whose definition in Merriam-Webster dictionary is “a: the movement, migration, or scattering of a people away from an established or ancestral homeland, b: people settled far from their ancestral homelands, and c: the place where these people live.” According to this definition, we can nowadays speak of the Syrian population outside Syria as a diaspora since they have been dispersed outside their home-land involuntarily as an aftermath of the Syrian revolution against the regime in March 2011 and the consequent barbaric atrocities that have been inflected by Assad regime and his allies on the Syrian civilians ever since, which forced more than four million Syrians according to UNHCR to flee the country and seek refuge in the neighboring countries first: Lebanon, Jordan, Turkey and Iraq, and in Europe and the US later http://www.unrefugees.org/2015/07/total-number-of-syrian-refugees-exceeds-four-million-for-first-time/?gclid=CjwKEAjw7ZHABRCTr_DV4_ejvgQSJACr-YcwqGsVqonNnITMYw1xal47am73r0iHjiySXhzDXx7MzxoCbX7w_wcB&gclsrc=aw.ds

For the past five years, the emergence of Syrian dialects has been substantially noticeable in CMC and the use of Syrian Arabic has rapidly and enormously expanded in the CMC of the Syrian diaspora. Parallel to the actual Syrian revolution which took place on the Syrian soil and which was mainly manifested by peaceful protests of civilians followed by a merciless war waged by Assad and his allies on the Syrian civilians, is a world-wide digital Syrian revolution in which all Syrians opposing the regime participated through Facebook posts, blogs, online magazines, YouTube videos and smart phone applications like Whatsapp and Viber among others in support of their fellow Syrians at home. Millions of pictures, videos, and posts have been circulating among Syrians on these platforms. Code switching from MSA to Syrian Arabic is always present in CMC among Syrians. They make a choice with every post, blog, article or comment between using MSA and Syrian Arabic. In addition to using other languages of course, depending on the audience, the type of message, the emotional status of the writer and other psychological, cultural and social factors.

In addition to these national stories and narrations, and the detailed records of and commentaries on the revolution, the resulting war, the socio-political complications, and the humanitarian crisis, there are always the personal and intimate stories of everyday happenings which family members and friends from different parts of the world share and comment on, on Facebook pages and WhatsApp. Even in this type of CMC code switching between MSA and Syrian Arabic exists.

On a personal level, and to give one concrete example, I have been an active user of Facebook and a participant in two WhatsApp groups: one including my immediate family in different parts of the world (Missouri, Massachusetts, Istanbul, Damascus, and Riyadh) and the second includes all my female friends in New Jersey the majority of whom are Syrians. The main topic of these two groups in addition to my posts and comments on Facebook since Friday September 30, 2016 was the passing of my sister in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The purpose of my blog is not to share my agony but rather to show how digital communication in the age of globalization which has coincided with the emergence and expansion of the Syrian diaspora has changed our customs and traditions relating to the circulation of and reacting to the news of a family death. My purpose is also to provide an example of how code switching is integrated into this kind of communication.

Circulating and reacting to a family or friend decease involves four emotionally charged social communicative acts:

1. Informing

2. Expressing sadness and loss (and even sometimes provoking sympathy)

3. Offering condolences and expressing sympathy

4. Offering gratitude and thanks to those who have expressed condolences

If we go a decade ago, before the wide spread of CMC and before the Syrian revolution and the resulting Syrian diaspora (this is still the practice inside Syria today whenever possible), when a family member passes away, there were two ways of informing family and friends: phone calls to the closest and most immediate members who on their part start reaching others in the social network of the deceased, followed by a hundred or so one-page printed obituary which are glued on walls of the buildings where the deceased and his family live and work. The phone conversations are carried out in Syrian Arabic naturally, however the obituary is typed in MSA.

Expressing sadness and loss on the one hand, and offering sympathy and condolences on the other were offered in person during three-day-gatherings at the house of the deceased following the burial ceremony. The main medium is again Syrian Arabic and the only presence of MSA is limited to some short formal condolence-offering clichés and to some citations from the Quran or quotations from the Prophet’s Hadith.

Today, the means and methods for carrying out these communicative acts have changed. Members of my family outside Riyadh, including myself, have been informed of my sister’s passing via a post on WhatsApp. Acts of mourning have been digitalized. All other related communications have been circulating on Facebook and WhatsApp. Syrian relatives and friends have offered their condolences on these two platforms from many cities in different states in the US, France, Germany, Emirates, Oman, Turkey, Syria, Lebanon and Saudi Arabia. In all of these communicative acts, both MSA and Syrian Arabic have been present side by side and have been linked by code switching.

In what follows are some instances of my posts and comments on Facebook in which the two codes have been used and in which code switching is sometimes present. Whether these switches are of type I, II or III according to Hinrichs, I leave it up to you to judge. I am giving a rough rephrasing of the meaning conveyed in the italicized English translations.

1. انتقلت آلى رحمته تعالى اختي الحبيبة الغالية سهير MSA/ FB profile picture

My dear beloved sister Suheir has moved to God’s mercy.

This comment accompanied a stock image which I used as my profile picture in which two verses from the Quran are cited along with a commonly used phrase.

2. انتقلت الى رحمته تعالى اختي الغالية سهير كنجاوي ام شذى وأنس وهيفاء. الى جنان الخلد يا حبيبتي. اللهم ارحمها وأسكنها فسيج جنانك وبدل سيآتها حسنات وعظم اجر اولادها وصبرهم يا الله. MSA/ FB post

My dear sister Suheir Kinjawi, mother of Shaza, Anas and Haifa, has moved to God’s mercy. May God have mercy on her, make paradise her residence, exchange her sins with good deeds, greatly reward her children and give them patience.

This post was accompanied with a picture of my sister, which is not the norm in traditional conventional printed obituaries.

3. MSA and English FB post

أمجد كنجاوي وريم كنجاوي فرج وناصر فرج وميس بجبوج كنجاوي ينعون إليكم خبر وفاة المرحومة سهير كنجاوي.

تقبل التعازي من النساء والرجال بأختنا الحبيبة المرحومة الأحد 2 تشرين الاول من الساعة الثانية والنصف بعد الظهر إلى الساعة الرابعة بمسجد ICPC.

Amjad Kindjawi, Reem Kinjawi Faraj, Mayss Bajbouj Kinjawi, and Naser Faraj are holding Azaa for their beloved sister tomorrow Sunday October 2 between 2:30 pm and 4:00 pm at ICPCtraditional.

Following the sociocultural conventions of the printed obituaries and in order to attach some gravity and weight to the initial act of informing MSA is used here in the above three FB posts

4. نتقدم بخالص الشكر لكل من تقدم لنا بالمواساة والعزاء شخصيا أو عن طريق مواقع التواصل الاجتماعي أو الهاتف. شكر الله سعيكم ولا فجعكم بعزيز

MSA/ FB comments

We extend our thankfulness to all those who offered sympathy and condolences personally, via social interaction media, or phone. May God reward your efforts and may you never mourn a person dear to you.

To give the post a formal and religious connotations, MSA is used here.

5.

شكرًا لكل اللي عزانا وواسانا بفقدان أختنا الغالية سهير رحمها الله وأسكنها فسيح جنانه. لا فجعكم الله على عزيز وشكر سعيكم

Code switching/ FB comment

Thank you to all those who comforted us and offered sympathy for the loss of our dear sister (Syrian Arabic). May God have mercy on her and make Paradise her residence. May God reward your condolences and prevent your mourning on a dear person (MSA)

The switch from Syrian Arabic to the Modern Standard Arabic marks a switch from my personal voice addressing my FB friends through a familiar and warm everyday expression of gratitude, to a prayer addressing God with a linguistic code associated with indirectly quoted formal prayers that have started as the voice of an identified or unidentified social source and then have become integrated in our own voice by time and repetition.

6. كان عندي أمل شوفك مرة تانية يا غالية وودعك بس قدر الله وماشاء فعل. عزاءي انك عند رب غفور رحيم كريم وأنك تركتي ذكرى طيبة وأولاد صالحين. رحمة الله عليكي يا سهير. Code switching / FB post

I had hoped to see you again my dear and say goodbye but (Syrian Arabic), ‘God had willed and He carried out His will’ (MSA). That you are by a forgiving, merciful, and gracious God, and that you have left us a good memory and good kids are my comforts. God’s mercy be upon you Suheir (Syrian Arabic).

While the main message from me to my sister is in Syrian Arabic, the quote cited here is in MSA. I have moved from my personal voice, to that of a voice of, an identifiable, concreate personal or textual source, as in Hinrichs Type II.

7. الحمد لله وصلت الرياض بالسلامة. والرحلة كانت مهونة من رب العالمين. شكرًا الكن حبيبات قلبي. بشوفكن على خير ان شاء الله Syrian Arabic/ FB comment

Thank God I have reached Riyadh safely and the trip was made easy by God. Thank you all my beloved. See you well God willing.

Since this message is intended to all my FB friends who have been following my posts and my trip to Saudi Arabic, Syrian Arabic is selected to express warmth and closeness.

In this blog I have attempted to offer my own examples for the use of two different varieties of the same language in computer-mediated communicative acts related to the loss of a family member, in an attempt to link my own experience with the argumentation that Hinrichs offers in his article.

The three assigned articles of Discourse, Context and Media, in the occasion of its special issue about “Digital Language Practices in Superdiversity”, form an interesting image of different phenomena that can be recognized around the key concept, superdiversity. This notion was first introduced by Vertovec around the middle of the last decade to cope with the challenges that poses to linguistics the increasing migration movements the globalized world brought with it.

The two cases presented (the first article is only a general introduction to the topic) are focused in contexts that could be thought as mirroring each other: in the first one, what is analyzed is the relationship between Dutch-Chinese teenagers and the language —that they barely master— of the country where their roots are: China. In this sense, this article is about leaving the identitarian language behind. In contrast, the next article deals with Luxembourg and, added to its already multilingual community (Luxembourgish, French and German) one can find not only English (a well established lingua franca) but also the language that each ethnic group brings with them (34.5% on the inhabitants of the country speaks 4 languages or more —page 76): here the experience is the clash that the already existing languages have with the new ones, particularly in the context of a Facebook group created with the purpose of giving and receiving objects without monetary exchange in return.

Regulation and normativity, on the other hand, complete the specular analogy: if one of the points that articulate the case of the Dutch-Chinese community is the different impositions the PRC has made (as still does) to the language, in the pursue of homegenizing the linguistic practices in the country (in this sense —but not only, according to the article— this is a top-bottom regulation), the other article shows how this type of attempt fails (in this case, requesting the opposite: diversity, i.e., always bilingual posts); and, finally, when the Facebook group gets acephalous (after a sort of funny coup d’état in the first anarchistic trial), the “natural” forces produced the contrary result: a vast majority of the posts ended up being solely in Luxembourgish. Linked to this, are two ontological problems about identity: the identity of the language and the identity of the people that speaks that language. In particular, these identities in the case of China seem to be reversed in comparison to the ones of Luxembourg. If in the first case we seem to have some sort of abstract national identity, regardless the fact they do not really speak the same language, in the second case what we have is a national identity that seems to be threatened and is in virtue of this that the language issue arises by imposing the (reactionarily) defined identity of Luxembourgish to the newcomers.

As a minor comment to this topic, there is something that seems to me worth noticing: the idea of the people of Luxembourg being “hospitable” as an explanation of their acceptance of using different languages with foreigners in the daily exchanges is, of course, unsatisfactory (not only because the non-scientific certainty that “hospitable” is not the word that best suits Europeans). Similarly, the idea that the PRC is a monster that tyrannically imposes their irrational whims to the passive people of China also doesn’t seem to work. Of course, a small economy as the one of Luxembourg, surrounded by strong economies as the French and the German ones, had to accept their participation in the country’s way of living, even in the most “identitarian” one, as the language is; needless to say, that is the reason why English is accepted as lingua franca in their business. Is exactly the same pattern the one that seems to explain why China needs to have a better communication system within its borders. Maybe this is why the imposition of Luxembourgish in the Facebook group did actually work: it is very likely to think that, having been money involved in that group, the identitarian protester would have accepted the bilingualism with a different attitude.

International Linguistic Association

Monthly Lecture Series

Tanya Karoli Christensen

University of Copenhagen

Vagueness in youth speech. Functional analyses of spoken Danish.

Saturday, November 12, 2016 at 11 AM – 12 PM

Borough of Manhattan Community College, Room N451

199 Chambers Street, New York, NY 10007

NOTE: All attendees will be asked to show some form of ID in order to enter the college.

Contact: Maureen Matarese, [email protected] www.ilaword.org

Young people have always been charged with ruining the language of their parents and grandparents by being sloppy and imprecise in their speech (and writing, for that matter). However, it has long been argued that ’vague’ language may serve a range of interactional functions (e.g. Kempson 1977; Dines 1980; Channell 1994; Gassner 2012). For instance, vagueness may arise because of unclear reference between a linguistic item and a class of objects, because a speaker (or her language) lacks an appropriate word for a specific concept, or because precision is uncalled for in the context.

Many different types of linguistic items have been categorized as vague in one way or another, including approximate quantifiers (about N), generic expressions (thing), general extenders (and stuff like that) and epistemic phrases (I think). Since the interpretation of vague expressions rests on context, many studies revolve around the semantics-pragmatics interface, but because vague expressions come in such great variety, sociolinguists have also studied such expressions as examples of so-called discourse variation (e.g. Cheshire 2007; Tagliamonte & Denis; Pichler 2010).

In this talk, I review data and results from a series of research projects related to different types of vague expressions in modern spoken Danish, i.e. epistemic adverbials (måske ‘maybe’) and epistemic phrases, general extenders, as well as the highly productive equivalent of English –ish (Dan: –agtig). The material I draw upon is the large and richly annotated LANCHART database of sociolinguistic interviews compiled during the 1980s and early 2000s.

On the backdrop of distributional data, I exemplify and discuss some representative uses of vague expressions in youth speech. One particularly interesting context is the elicitation of language attitudes. The task of categorizing other people on the basis of their speech is obviously a face-threatening act (Brown & Levinson 1987), and informants orient to this by couching their descriptions in vague terms (1-2).

(1) altså måske er de lidt mere landlige ovre i Jylland men jeg ved det ikke rigtigt

I-mean maybe they are a-bit more rural over in Jutland but I don’t really know

(2) det er sådan lidt mere … slang … og bare … go with the flow-agtigt … end det der andet

it is like a-bit more … slang … and just … go with the flow-ish … than the other one

The Androutsopoulis-Juffermans Editorial calls for us to be wary of the “happy heterogeneity” theory of the Internet as a vast sphere of superdiversity, where many disparate people, languages, and attitudes coexist and mesh together. Rather, the Internet can be recast not as a monolith but a collection of new technologies which independently impose different structures on its users, to varying effect.

So to what extent can superdiversity be said to exist in a communicative act such as writing on a forum or social media? Is there an inherent pressure to adopt a greatest common factor of language so that the largest number of people can understand each other? How is this diminished by the ability of niche groups to collect and communicate outside the linguistic norm they’re otherwise submerged in? While individuals may find support and solidarity this way, it still represents a diminishing diversity, ostensibly, a forum is circumscribed by its language, and individuals will remove themselves from those they can’t read and immerse themselves in those they can. Even an internet taken holistically is a strange solute, where bubbles of smaller languages float in a larger dearth of English or other dominant voices, with more or less osmotic membranes between them. But even within these bubbles, the languages are isolated and unified. It’s at their borders where actual superdiversity of language can exist. In a situation where multiple language are in play, a limiting pressure exists so long as any reader doesn’t understand one or more language, and the forum’s lingua franca naturally becomes the language with the most communicative power. Its use can be expected to rise.

The Belling article shows a longitudinal example of this process as a gifting forum moves from its inception through a period of maturation and multilingualism before a glitch renders it anarchic and eventually monolingual. In this case it was authority by moderators were attempted to maintain multilingualism on the site, and populist pressure which demanded monolingualism. There may be room for a study on just how multilingual forums are sustained on the internet, and whether their purpose (say, individuals wishing to practice one language or the other) influences how long they last. In a case such as the Luxembourg gifting forum, the multiple language were felt by many to impede the purpose of the forum. Separating this reasoning from political feelings is tricky, as both produce the same pressure towards monolingualism but come from different ideological roots. In studies throughout this course we’ve seen how eager individuals are to police themselves and each other’s speech, and so old prejudices of the written word linger and find new life on the same forums which were meant to emancipate language from these restrictions.

We’re presented then with the interesting state that Ibtisam has touched on in her previous blog post, of Ausbau languages as a potentially bottom-up construction, and their conflict with the traditional top-down imposed Ausbau language of nation states interested in unity. The Lexander article shows a profoundly interesting example of a community dynamically forging and adapting the languages at its disposal to fulfill the new role of texting in their society. Rather than compete with state-imposed standards of literacy, it coexists with it. “Through acting as mediators and as instructors, the young are put in power” this is a profound reversal of the traditional dynamic, where young people are imbued with language rules from elders and authorities, and then play and experiment with language on their own. Instead, their experimentation influences their elders, but the fact that widespread standards still arise points to the resilience of language.

This would seem to go against the claim by Androutsopoulis that technology facilitates rather than creates the interactions we see among groups seeking to communicate more frequently over longer distances. The notion of a young class of CMC-enabled people instructing their elders defies much of history, but the results are seen throughout the internet where new standards are continually being tested, warped, and reforged.

Hello all,

I recently went out from Facebook because I’m pretty busy and felt overwhelmed for all the politics and hatred in the world. Last night I entered back for some minutes. I found this new Moby’s videoclip. I watched and I closed my account again.

I hope you find this song interesting (as I did). It’s all about the dark side of CMC. 🙁

See you soon (off-line)!

A handful of “beauty boys” have primped and preened their way into the female-centric world of Instagram and YouTube makeup artistry—and the cosmetics industry wants in.

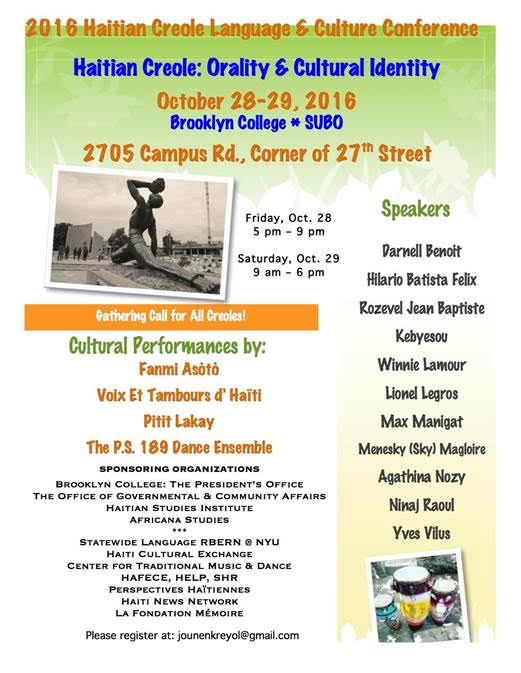

“Haitain Creole: Orality and Cultural Identity”

Friday, October 28th 5:00 p.m.-9:00 p.m., and Saturday, October 29th, 9:00 a.m.-6:00 p.m.

at Brooklyn College, 2705 Campus Road

See below for events, and how to register!

As today’s readings focused on “digital enregisterment,” I wanted to share some pieces of a paper I have been working on that deals with this same phenomenon. As most of my recent research deals with performers (particularly women) in the adult industry, I think the concept of voicing and enregisterment in a CMC setting is particularly relevant as performers are characterized as both individual and social types by an audiences whose only interaction with them is mediated by online representation, either in the form photos, videos, personal websites or webcam sessions. The paper I want to share analyzes the online marketing strategies of the #1 top-selling male sex toy, a synthetic rubber vagina called the Fleshlight, and it’s line of toys modeled after female porn stars, called “Fleshlight Girls.” :

Fig 1.

While the popularity of the Fleshlight seems to support acceptance of a disembodied vagina as replacement for the whole, the semiotics of the brand’s marketing strategies suggest that more is necessary for the experience of simulation to be complete. Much of the company’s success has come through the addition of a line of products called Fleshlight Girls, where each Fleshlight is cast from the external genitalia of a different porn star and consumers pick products based on their favorite girls. The branding of the Fleshlight Girls goes beyond a realistic casting of the girl’s external genitialia however, as the company offers an opportunity to “Get inside today’s hottest stars,” a promise that points to the individuation of the Fleshlight Girls’ internal anatomy as well. While the site states that “each custom-molded Fleshlight Girls masturbation sleeve is an exact mold of each star’s most intimate parts,” the textures of the internal sleeves, though unique for each girl, are not modeled after their physical anatomy, a process that would be impossible to realize[1]. Instead, an iconic resemblance relationship is established through a semiotic linkage of text descriptions and accompanying images, which map the textures of the rubber sleeve onto the girl it represents.

The discursive work of the company’s website can also be described as voicing, with photos of the girls and descriptions of the Fleshlight itself serving as the entextualization necessary for voicing to occur. Though in defining voicing, Bakhtin (1981, 84) focused on the ways in which utterances index particular social or individual types, applications of voicing have since expanded to include a number of other semiotic channels. Agha’s concept of “figures of personhood” (Agha 2005), recognizable (linguistic and non-linguistic) signs that index social or individual types, is particularly relevant here. This illustrated in the following example:

Fig 2.

CHRISTY MACK: ATTACK

Featuring a design as wild as Christy’s tattoos, these dots and bumps will make your bad girl porn fantasies come alive.

On the Fleshlight website these “figures of personhood” are both emerge visually in the images of each girl and her respective inner sleeve, as well as discursively in the product descriptions and bios of each Fleshlight Girl. First, the image of Christy: her tattoos; her mohawk hairstyle; the heavy chain jewelry she wears around her neck and waist; as well as the metal cuffs on her wrists all function as semiotic material for the voicing of Christy’s character. Beside her are two images of the Fleshlight Sleeve itself, both the exterior which we know is a realistic mold cast from Christy’s vagina, as well as a cross-section of the inner layout of the sleeve. Though the textures alone might not be discernible as indexical of the same qualities as the image of Christy, the description below makes the connection clear: “featuring a design as wild as Christy’s tattoos, these dots, bumps, ribs and nodes will make your bad girl fantasies come alive.” Though we are meant to assume automatically that the inner texture of the sleeve is representative of Christy in some way, it is through the discursive work of the product description that the Fleshlight company elucidates the relationship more explicitly. Through the naming of specific visible qualities from the photo of Christy (her tattoos) along with characteristics of the sleeve texture (“dots, bumps, ribs, and nodes,”) the qualities of being “wild” and a “bad girl” are mapped onto both. Altogether, the description of the inner sleeve’s texture and it’s co-presence with the image of Christy and the Fleshlight itself create a semiotic totality through which Christy, and her respective Fleshlight are voiced as having the qualities of “wildness” and being a “bad girl.” As discussed in the Agha article we read, this voicing is both “social” and “individual” as it relies on the recognizability of signs as indexical of particular social types, while at the same time involves individual voicing through the “biographic identification” of Christy.

This is just one example from my analysis, and I would happy to be share more if anyone is interested! I had not encountered work on digital enregisterment at the time of drafting this piece but I think it is relevant to explore. I felt that the two readings (not Agha) that focused on this were functional examples but did not delve deeply into the differences between online and offline enregisterment practices. This is something I have questions about, as I firmly believe that especially in regards to my topic of pornography the estrangement of physicality is essential to the interaction and I wonder how that applies to other (perhaps less taboo) CMC settings.

[1] https://www.fleshlight.com/fleshlight-girls/fleshlight-toys/